The Veteran

As they drove by, they spat at him. They flung half-filled beer cans and called him names. He was nineteen and wore an American uniform. His number had been drawn in the draft. #14. He knew he would be headed to Vietnam. But he was not afraid. His father and his mentor Chuck had both served in World War II and Korea. They made him proud.

It was 1970 and although he knew Vietnam was an unpopular war, he did not know he would be reviled when he donned the uniform. “I was a kid, and I didn’t fully understand the war,” he told me not long ago, “but I did understand duty, and I had grown up an American. I loved and wanted to serve my country.” His voice softened, “But the beer cans . . . the hate being flung at you from fellow Americans back then . . . I didn’t expect that.”

Yesterday I sat in an elementary school gym packed with children celebrating Veterans Day by singing “American Tears.” Several hundred children belted out, “Sometimes I think about America, about her struggles through the years.” It gave me pause. I love my country, but of late I have not always celebrated living here. Like many of you I am frustrated with our inability to act on global warming and to protect our children from shootings and bigotry. I am upset with the elected officials who waste time quibbling when so much is at stake.

Suddenly on the wall of this gym appeared a huge slide of a Vietnam veteran. Of course, Vietnam was the first time I questioned my country. I would come home from high school and see the images of the atrocities played out on our television screen. I wrote a high school essay, decrying our obsession with war, especially one that lacked logic.

But the children’s lilting voices broke through my reverie. They sang, “I think of people who did what they had to do with the strength to act through their fears.”

In that gym I was sitting by a man I admire deeply. The veteran. The one who was spat at by fellow Americans several decades ago. One who believed in the ideals of our democracy and would have given his life for those ideals. The one I married. In that moment, the words to the song I heard resonated deeply in me, “I know I’m blessed to be living in liberty.”

In that gym I was sitting by a man I admire deeply. The veteran. The one who was spat at by fellow Americans several decades ago. One who believed in the ideals of our democracy and would have given his life for those ideals. The one I married. In that moment, the words to the song I heard resonated deeply in me, “I know I’m blessed to be living in liberty.”

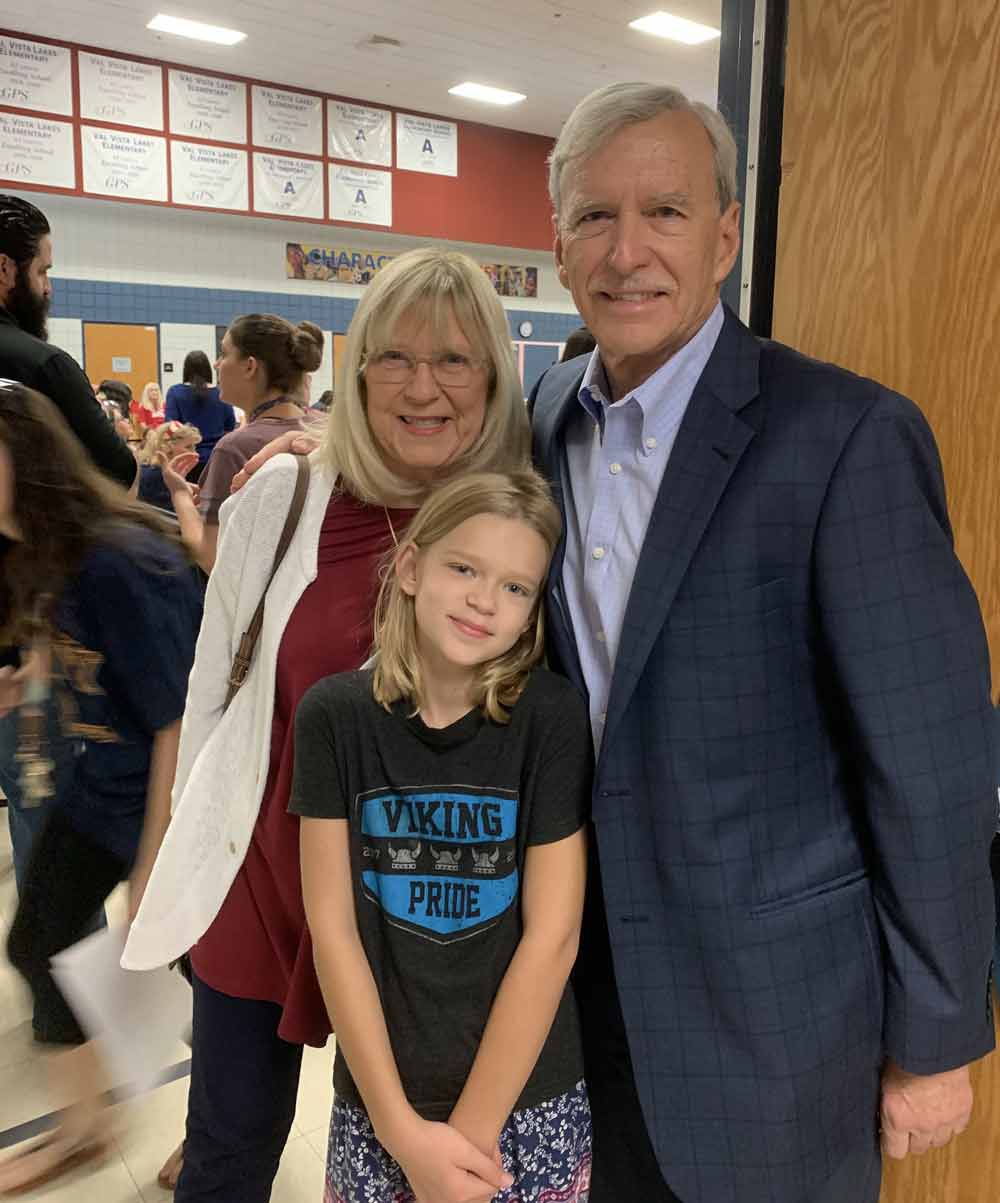

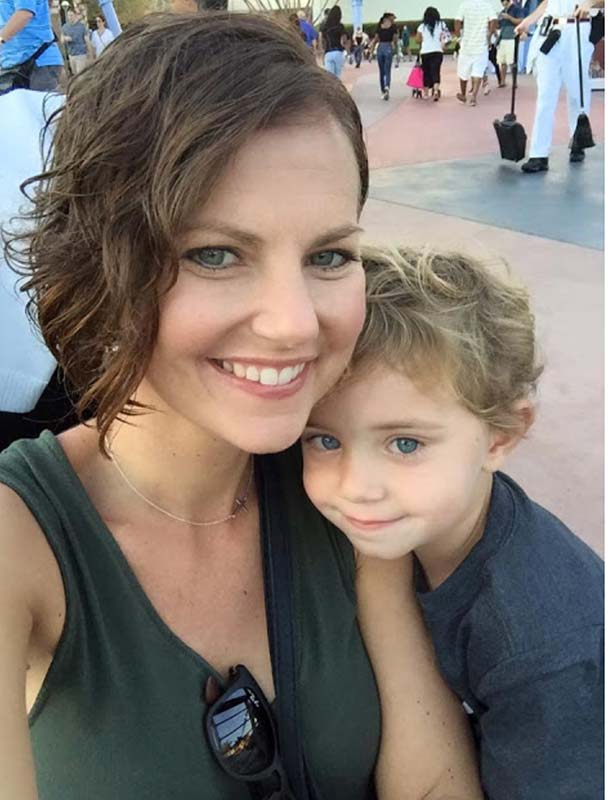

When the children stopped singing, my granddaughter returned to sit in the special section set aside for her grandfather. My husband. The veteran. She beamed at him with pride. She had stayed up late last night making a poster to honor him. The veteran was introduced to the school and the children clapped wildly in appreciation for his service.

In that moment, I realized it is true. I will always be an American—and the tears I cried were heartfelt American tears. The veteran was sniffing back tears, too. Tears of joy.

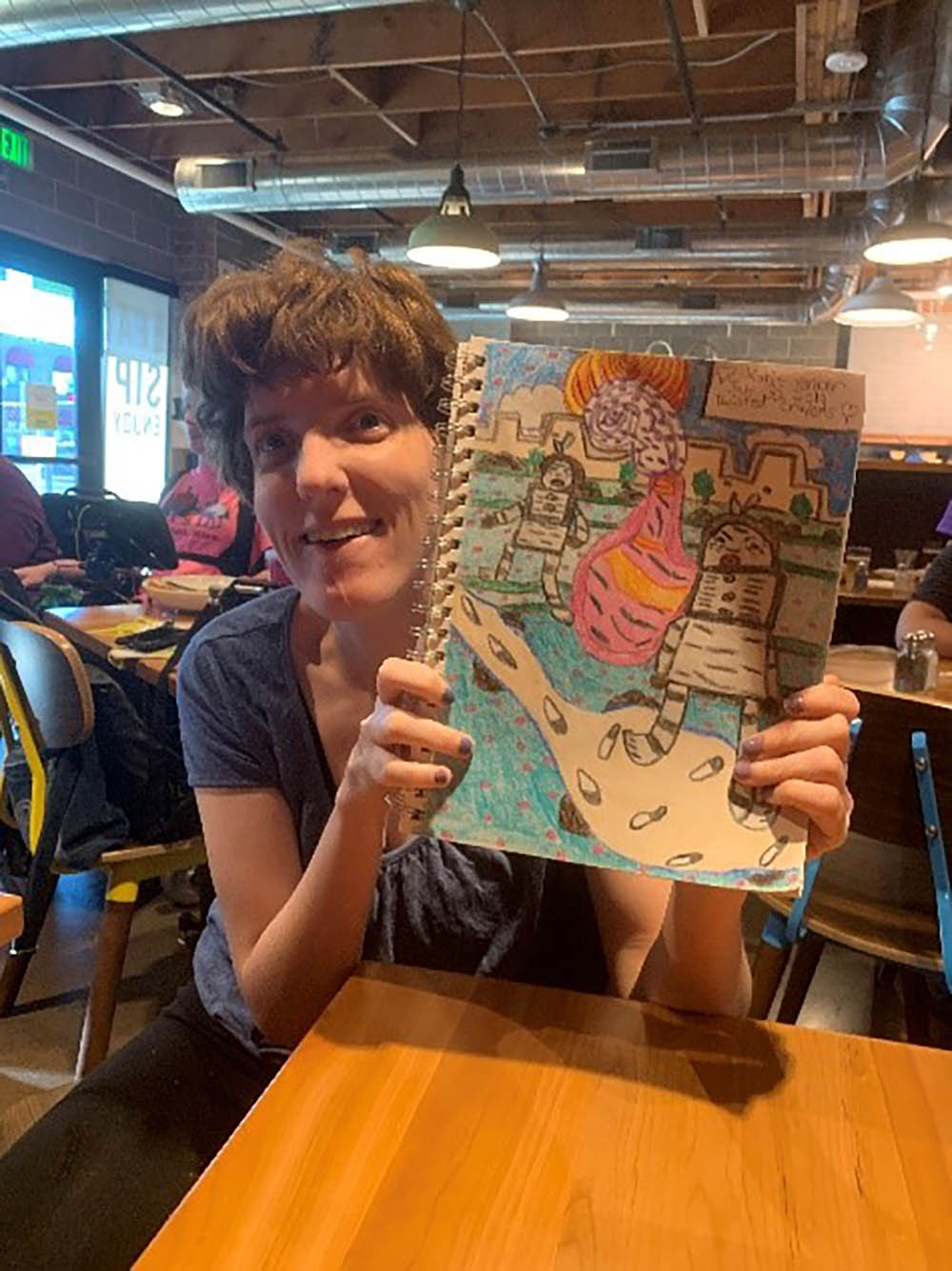

Katie held up her portfolio of drawings, pleased that I had asked to see them. I had been invited to an evening of “Stories of Ourselves.” I wanted to learn how those with language disabilities shared their stories. Katie, born with cerebral palsy, became my joy-filled teacher.

Katie held up her portfolio of drawings, pleased that I had asked to see them. I had been invited to an evening of “Stories of Ourselves.” I wanted to learn how those with language disabilities shared their stories. Katie, born with cerebral palsy, became my joy-filled teacher.