Unexpected Kindness

In 1982 writer Anne Herbert scrawled a few words on a placemat in a Sausalito, California restaurant. “Practice random acts of kindness and senseless acts of beauty.” Eventually her words set off a chain reaction of kindness. Just this morning the guy in front of me at the Wildflower café bought my coffee. I could not stop thinking how thoughtful this was as I headed back to my study to dig through my old files.

Today I awoke on a mission. I want to find my words. I am trying to thread together pieces that might form my next book. I have had a couple of false starts. It is a long and tedious task. Sometimes I feel like I am scaling Mount Everest, but if I get it right, my current scrawls will become a book. Writing helps me find meaning. Find wholeness. Explore my unique voice. Learn. The work gives me purpose, and I know I am driven to do it for others—not simply me. But I am unclear why I must tirelessly tunnel through mounds of old papers to do it .

Maybe I need to control the space around me? Maybe I need a sense of order? But I realize that I simply need space to hold my new ideas when I am not tinkering with them or shuffling them into a different pattern or plan. I need a home for this creation as it evolves.

When I open the top drawer of my file cabinet, I find stacks of old tax papers that show how little money a writer can accrue in whole years. The first file drawer empties with ease as I stuff this papery mass into a plastic garbage bag that becomes so stretched it begins to split.

In the second drawer I discover the draft of an adolescent novel that I had titled Outcast. It is the story of a boy in high school trying to find himself while struggling with his obsessive-compulsive disorder. My friend Margot had quilted a potholder to celebrate the birth of this book. It frames all things writerly—paperclips, manuscripts, coffee cups, pens, and a huge sign that holds my mantra, “YOU CAN” —for she believed in the book even before I did. While my son would talk me out of publishing it because he feared it was his story, I would publish a truncated version of it later. I hug the trivet to my heart knowing it is another kindness. I will put it to use in my kitchen!

In the bottom drawer I find two oil paintings that I had planned to hang. When the pandemic hit, my neighbor Candy could no longer volunteer to care and rock the babies in the nearby hospital’s NICU, and she decided to learn to paint. Then a small tissue wrapped oil-painting of a green and pink-bellied hummingbird showed up at my doorstep. After my mother’s death, I had told Candy that a hummingbird often seems to pause at my window where I write. In the note accompanying her painting, Candy wrote, “Many believe when a hummingbird visits, it is a visit from a loved one who has passed.” The painting is small and delicate. Like the bird who visits me. I position it on my windowsill overlooking my garden because I will be able to see at least one hummingbird each morning.

But all the while I kept thinking of one word.: Kindness. One study from Emory University shows us that when you are kind to others, you raise the level of feel-good hormones created in your brain. In other words when you act altruistically toward others, you are rewarded with what is called a “helper’s high.”

Perhaps even more important is that when others are kind to us, we will be inspired to do kindnesses, too. There seems to be a ripple effect that comes with kindness. That is why Anne Herbert’s beautiful words scribbled on a napkin have echoed back to us through the years. This is why after I received the hummingbird painting, I gave my neighbor a copy of my book, The Story You Need to Tell. To reciprocate.

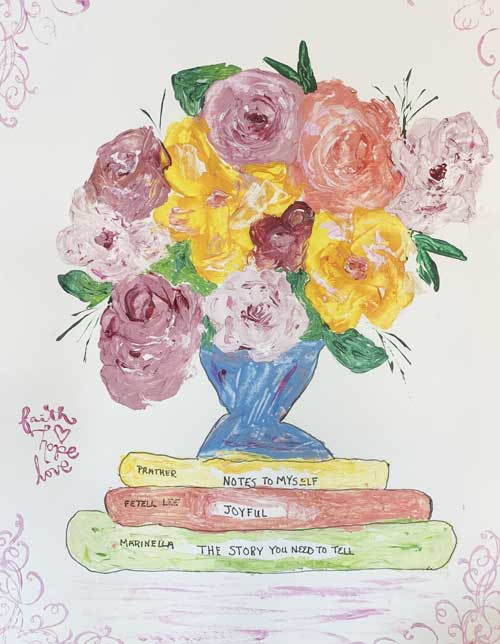

Weeks later I found a larger painting wrapped in tissue in a box by my front door. I unwrapped it to discover another oil painting. Etched on the canvas was a small vase with bright colored roses made vivid with shadowing and positioned on a nightstand by Candy’s bed. Beneath the flowers, my friend had carefully painted a stack of three books– Notes to Myself by Hugh Prather, Joyful by Ingrid Fetell Lee, and The Story You Need to Tell. For my friend to read my book was a kindness, but to honor it in her work was truly moving for me.

As I finished shoving old notes from books-past into garbage bags and hauling them outside to the recycle bin, I paused for a break and in that moment, it hit me that I find writing a book is a long, hard endeavor. Like climbing that mountain or competing in the Olympics. But I will go back to my study because there are moments of powerful insight and revelation and moments of what I have come to know as the miracles of words. When Anne Herbert wrote “practice random acts of kindness” she experienced this. Her words have echoed through the decades and danced through my mind yet again this morning and as I write this blog.

In the end what matters more than waving the older lady with very few groceries ahead of you in the grocery line or taking dinner to a friend who has lost a loved one or simply helping a child retrieve a lost toy tossed from a highchair at a restaurant? Today and every day I am going to work a little harder to appreciate the moments of unexpected kindnesses–a cup of coffee, a handmade potholder, or heartfelt oil paintings. Those wonderful moments come ripe with encouragement. With hope. With friendship. With joy—and with the gratitude that is now spilling onto this page. Let’s continue to surprise each other with unexpected kindnesses. It makes all the difference.